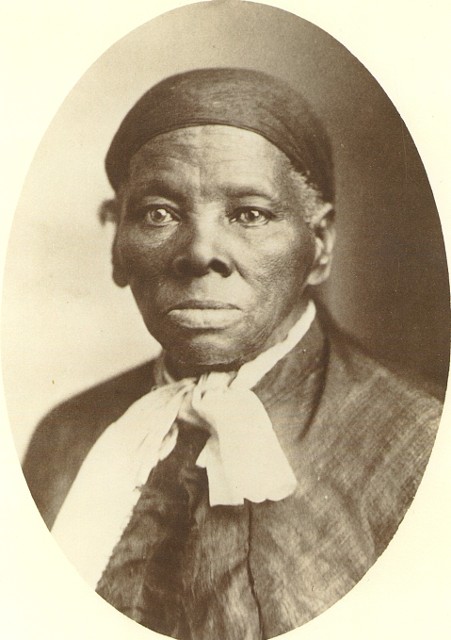

Originally named

Araminta, or “Minty,” Harriet Tubman was born on the plantation of Anthony

Thompson, south of present day Madison and Woolford in an area called Peter’s

Neck in Dorchester County, on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. Tubman was the

fifth of nine children of Harriet “Rit” Green and Benjamin Ross, both slaves.

Ben Ross was a timber inspector who supervised and managed Thompson’s

significant timbering interests on the Eastern Shore, earning him a reputation

as a highly prized and respected bondsman. Thompson, a successful planter and

businessman, enslaved more than forty African Americans during his lifetime.

This slave community, and the free and other enslaved black communities that

provided the labor for the white planters in the Peter’s Neck area, constituted

the familial and social world of Harriet Tubman and her family.

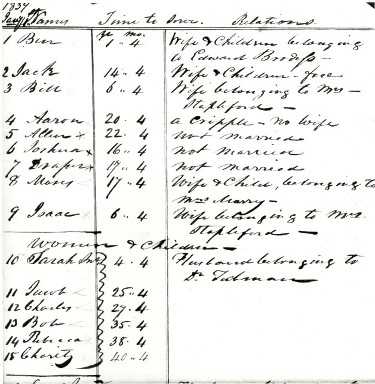

Thompson’s second

wife, Mary Pattison Brodess, and her young son, Edward, legally owned Tubman,

Tubman's mother and siblings. It was through Thompson’s marriage to Mary

Brodess that Ben Ross and Rit Green met, finally marrying and starting their

own family around 1808. According to laws enacted during the seventeenth century

in the American colonies, any children born to an enslaved woman were

automatically slaves, and ownership fell to the mother’s owner, even if the

father was a free black or a white man. Ben and Rit’s family grew over the next

few years; Linah was born about 1808; she was followed by Mariah Ritty in 1811,

Soph in 1813, Robert in 1816, and then Minty, or Harriet Tubman, in 1822.

Thompson had

married Edward’s widowed mother when Edward was a small child, and after she

died in 1810, Thompson became young Edward’s guardian. Thompson remained in

that role until Brodess reached the age of twenty-one in 1822, the legal age at

which Edward could claim independence and his rights to his inheritance, which

included Rit and her children. By 1824, Tubman, her mother, and her siblings

were forced to move away from Ross and the Thompson plantation, to Brodess’s

own farm in Bucktown, a small agricultural village, ten miles away. Though

separated from their father, Tubman and her siblings maintained strong bonds

with the black community surrounding Thompson’s plantation, which provided a

consistent and nurturing force throughout Tubman’s unstable childhood and young

adulthood.

Tubman’s family

eventually grew larger with the addition of another sister, Rachel, born around

1825, and three more brothers, Ben in 1823, Henry in 1830, and Moses in 1832.

Tubman later recalled having to care for her younger siblings when she was as

young as five years old, while her mother was forced to leave them alone in

their cabin while she worked in the “big house,” as the master’s home was

called. The dangers inherent in leaving such young children alone to fend for

themselves was just one of the many daily threats and injustices endured by

enslaved families.

Tubman said that she spent little time living with Brodess; he often hired her out to

temporary masters, some of whom who were cruel and negligent. She recalled

being whipped daily as a very young child by an exacting mistress, who left

scars still visible eighty years later. She was also forced to labor in icy

cold winter waters setting muskrat traps. This work made her so weak and sick

that she was repeatedly returned to Brodess as useless. Once restored to health by her

mother, Tubman would be hired out again and again. These separations from her

family exacted a heavy toll on her, and she suffered intense loneliness and

fear throughout her childhood. Brodess, in the meantime, also hired out other

members of Tubman’s family; his farm was too small to productively use all the

enslaved labor he owned. Brodess also sold some of his enslaved people,

including three of Tubman’s sisters, Linah, Mariah Ritty, and Soph, to

out-of-state buyers, permanently fracturing her family. Linah and Soph were both forced to leave young

children behind.

At this time, the

Eastern Shore of Maryland was experiencing a significant agricultural and

economic decline. The invention of the cotton gin (in 1793) drove rapid expansion into

the Deep South and southwest territories during the early part of the

nineteenth century, as farmers rushed to clear and develop land for cotton

production.

The cultivation

and harvesting of cotton required a large labor force, and the demand for

enslaved labor to work these vast cotton plantations grew rapidly. The

trans-Atlantic slave trade (from Africa to North America) had been declared illegal in 1808, leaving

intra-regional slave trading as the only legal option for expanding southern

agricultural interests desperate for labor. On the Eastern Shore, the

transformation from tobacco production, which required a large full time labor

force, to one of grain production, which required less labor-intensive work,

created a surplus of enslaved labor. Slave owners throughout the Chesapeake

region found a ready market for their enslaved people, and thousands from the

Eastern Shore were torn from their families and sold to work in the cotton and agricultural fields of the Deep South.

The loss of Linah, Mariah Ritty, and Soph brought great sorrow and anger to the Ross family. Brodess

turned the proceeds from their sales into land purchases to expand his own Bucktown

farm. This injustice was only compounded by Brodess’s refusal to liberate Rit

when she was forty-five years old, as required under the will of his

great-grandfather, Atthow Pattison, who had owned Rit when she was a child. Brodess claimed Rit through his dead mother's and as the heir to Pattison’s estate. Tragically, he refused to

honor his obligation to free Rit under the terms of Pattison's will, which also provided

for the liberation of Rit’s children once they reached the age of forty-five as

well.

It was late fall, sometime

between 1834 and 1836, when Tubman was nearly killed by a blow to her head from

an iron weight, thrown by an angry overseer at another fleeing slave. Tubman

had been hired out as a field hand to a neighboring farmer, and one evening she

was called to accompany the plantation cook to the local dry goods store to

purchase items for the kitchen. When they arrived at the store, Tubman

attempted to block the path of the overseer who was in pursuit of a defiant

slave boy. The overseer picked up a weight from the store counter and threw it,

intending to fell the fleeing young man, but it struck Tubman with such

crushing force that it fractured her skull and drove fragments of her shawl

into her head. Near death, she was forced to return to work in the fields.

Seventy years later Tubman told a friend, Emma Telford, “I went to work again

and there I worked with the blood and sweat rolling down my face till I

couldn’t see.” She was quickly sent back to Brodess, who attempted to sell her,

but no buyer was interested in purchasing a sick and wounded slave. “They said

they wouldn’t give a sixpence for me,” Tubman later told Sarah Bradford,

another friend and early biographer. The severe injury left her suffering from

headaches, seizures, and periods of semi-consciousness, probably Temporal Lobe Epilepsy,

which plagued her for the rest of her life.

This injury

caused her great pain and suffering. The head injury also coincided with an explosion of

religious enthusiasm and vivid visions, which eventually took on an important

role in Tubman’s life. This intense spirituality, punctuated by potent dreams

that she claimed foretold the future, influenced not only her own courses of

action, but also the way other people viewed her. Tubman’s religiosity was a

deeply personal spiritual experience, unquestionably rooted in powerful

evangelical teachings, but also reinforced and nurtured through strong African

cultural traditions. She and her family probably integrated a number of

religious practices and ideas into their daily lives, such as Episcopal,

Baptist, and Catholic teachings, all religious denominations supported by local

white masters intimately involved with Tubman’s family. Many slaves were

required, like Tubman’s family, to attend the churches of their owners and

temporary masters.

Whatever her place

of worship, there can be no doubt Tubman’s faith was deep and founded upon

strong religious teachings. Thomas Garrett, a famous Underground Railroad

agent, later wrote of Tubman that he “never met with any person, of any color,

who had more confidence in the voice of God, as spoken direct to her soul . . .

and her faith in a Supreme Power truly

was great.” Regardless of the exact nature of Tubman’s religious instructions,

daily survival remained her biggest challenge. Her profound faith and the care

and nurturing of family and friends helped her survive her darkest hours.

After a lengthy

recovery period, Tubman was hired out to John T. Stewart, a Madison, Dorchester

County, farmer, merchant, and shipbuilder, bringing her back to the familial

and social community near where her father lived and where she had been born.

Laboring first in Stewart’s house, she soon began working in his fields, docks,

and timber yards, exhibiting great feats of strength and endurance. Enslaved

women often preferred outdoors or fieldwork, if only to escape the tyranny of

demanding mistresses and the sexual advances of white men in the household.

Brodess eventually allowed Tubman to hire herself out, after paying him a

yearly fee of sixty dollars for the privalege to work for herself. This allowed her to earn

enough money to buy a pair of oxen, enabling her to maximize her wage earning

potential, and perhaps offering the possibility of one day buying her own

freedom.

Being close to her

father also brought other rewards. Through him, and through her work on the

docks and on a timber gang, Tubman learned the secret networks of communication

that were the provenance of black men, particularly black mariners. Tubman became

part of an exclusively male world. Here, beyond the watchful eye of white

masters, Tubman’s father and others passed along the map of communication

networks of black mariners whose ships carried the timber and other goods to

the Baltimore shipyards. They were part of a larger world of towns and cities

up and down the Chesapeake Bay, into Delaware, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey.

They knew the safe places and, more importantly, they knew the danger. Tubman’s

unique ability to effectively use this complicated network, combined with

well-practiced skills of disguise and deception, would help her act on her own

growing consciousness of the horrors of slavery. “Slavery,” she said, “is the

next thing to hell.”

Around 1844, Minty Ross married John Tubman, a free man at least five years her senior. John had been born to free parents, but like many of his siblings and other friends and relatives, he married an enslaved woman with whom he had no legal rights. Because Minty was enslaved and legally owned by Edward Brodess, and though her marriage was spiritual and accepted by the community within which she lived it had no legal standing. Any children born to them would have become the property of Edward Brodess - neither John nor Harriet had any rights to them. They could be sold or given away at the whim of Edward Brodess. John Tubman could have marrried a free woman - half the black population of about 9,000 people in Dorchester County at that time were free - but his love for Harriet must have been strong for him to forfeit any rights he might have as a husband and a father.

When Edward Brodess died in March 1849, the security of Harriet and John's life together was threatened. Knowing she was about to be sold, Tubman fled to freedom without him. She soon learned he was not interested in joining her in the North, and he married another woman in the community - a free woman named Caroline with whom he had four free children. Broken hearted, Tubman, refusing to sacrifice her freedom by returning and fighting for her marriage, instead committed herself to liberating her family and friends. From 1850 to 1860, Tubman would return to Maryland to rescue scores of family and friends. For more information on her own escape and rescue missions along the Underground Railroad, click on the tabs "Harriet Tubman's Flight to Freedom" and "Harriet Tubman and the Underground Railroad" above.

In the early

spring of 1858, Tubman met the legendary John Brown, a radical abolitionist and

fiery freedom fighter, at her home in St. Catharines, Ontario, Canada, where she had settled with her brothers, parents and other runaways from American slavery. Tubman’s remarkable

ability to travel undetected in slave territory piqued Brown’s interest; he was

so impressed by her genius that he referred to her as “General Tubman.” She

became a devoted supporter and confidante, helping Brown plan to liberate

slaves through a surprise attack on the federal arsenal at Harper’s Ferry,

Virginia in 1859. Possibly ill and unable to travel at the appointed time,

Tubman was not by Brown’s side when he launched his attack in October. Brown

and most of his small band of fighters were killed or later hanged for treason.

Tubman believed, however, that Brown was a martyr for freedom, and that he was

the greatest white man she had ever met.

The winters in St.

Catharines, Ontario, Canada were too severe for Tubman’s parents. In 1859, William Henry Seward, Lincoln’s

Secretary of State, sold Tubman a home on the outskirts of Auburn, New York,

where she settled her aged parents and other family members. Surrounded by

ardent abolitionists, such as Martha Coffin Wright and Gerrit Smith of

Peterboro, Tubman’s family was supported and protected. Money was a constant

worry for her, though. Tubman turned to the antislavery lecture platform as a

means to raise money for both her family and her missions. Starting in the

spring of 1858, she became a fixture at abolition and suffrage meetings

throughout Central New York and the Boston area, sometimes under the pseudonym

“Harriet Garrison” to protect her from slave catchers. Increased vigilance on

the part of slaveholders on the Eastern Shore made her more vulnerable to

capture, and return trips to rescue the rest of her family became too risky.

But she continued to fight against the slave system. On her way to Boston in

April 1860, Tubman became the heroine of the day when she helped rescue a

fugitive slave, Charles Nalle, from the custody of United States Marshals charged

with returning him to his Virginia master under the provisions of the Fugitive

Slave Act of 1850 (see: Freeing Charles by Scott Christianson for more exciting details of this remarkable story.)

Tubman became

politicized very early on, attending antislavery meetings, black rights

conventions, and women’s suffrage meetings throughout the latter part of the

1850s. It was not long before Tubman found herself challenging women’s and

African Americans’ inferior political, economic and social roles. A trustworthy

network of active reformers, such as abolitionists and suffragists Lucretia

Mott, Susan B. Anthony, Martha Coffin Wright, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper,

Ednah Dow Cheney, Caroline Dall, and activists Frederick Douglass, Lewis

Hayden, John Rock, William Wells Brown, William Lloyd Garrison, Franklin

Sanborn, and Wendell Phillips, proved worthy in Tubman’s eyes. They were

devoted to equality and justice, and they often risked their own lives and

livelihoods to defend and protect runaway slaves. Among them she found respect

and the financial and personal support she needed to pursue her private war

against slavery on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. The ideologies of racial and

gender equality, which Tubman incorporated into her life during the 1850s, would become central to her activism for the remainder of her life.

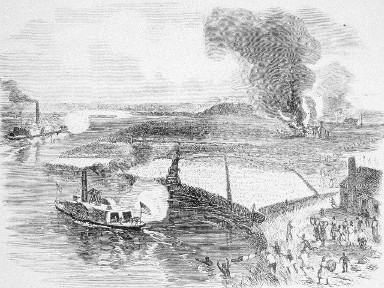

Tubman’s total commitment to

destroying the slave system eventually led her to South Carolina during the

Civil War, where she alternated her roles as nurse and scout, cook and spy, in

the service of the Union army. Eventually, she became the first American woman

ever to lead an armed raid into enemy territory. In early 1862, Tubman joined

Northern abolitionists in support of Union activities at Port Royal, South

Carolina. Throughout the Civil War she provided badly needed nursing care to black

soldiers and hundreds of newly liberated slaves who crowded Union camps.

Tubman’s military service expanded to include spying and scouting behind

Confederate lines. In early June 1863, she became the first woman to command an

armed military raid when she guided Colonel James Montgomery and his Second

South Carolina Black regiment up the Combahee River, routing out Confederate

outposts, destroying stockpiles of cotton, food and weapons, and liberating

over seven hundred slaves.

Later that summer, Tubman witnessed

the carnage inflicted upon the all-black Massachusetts Fifty-Fourth Regiment on

19 July 1863, at Fort Wagner. She later told an interviewer that she served the

regiment’s white colonel, Robert Gould Shaw, his last meal. She had become

quite familiar with Shaw and his regiment, which included Frederick Douglass’s

two sons, Lewis and Charles, since they had arrived in Beaufort six weeks

before. Tubman’s description of that fateful day would long be remembered: “And

then we saw the lightning, and that was the guns; and then we heard the

thunder, and that was the big guns; and then we heard the rain falling, and

that was the drops of blood falling; and when we came to get in the crops, it

was the dead that we reaped.” Union losses were horrific: 1,515 dead, wounded,

missing, or captured, compared to only 174 Confederate casualties. The injured

were transported to Beaufort, where Tubman provided nursing and comfort to

hundreds of casualties.

After the war, Tubman returned to

Auburn, New York. There she began another career as a community activist,

humanitarian, and suffragist. In addition to providing a home for numerous

friends and relatives, she also worked to raise money for the Freedmen’s

Bureau, which had been established to provide education and relief to millions

of newly liberated slaves. In 1869, a local author named Sarah Bradford

published a short biography titled Scenes

in the Life of Harriet Tubman, bringing brief fame and financial relief to

Tubman and her family. Tubman married Nelson Davis, a veteran, that same year;

her husband John had been killed in 1867 in Dorchester County, Maryland. She

struggled financially the rest of her life, however. Denied back pay for her

scouting services during the Civil War, she did receive a widow’s pension as

the wife of Nelson Davis, and, later, a Civil War nurse’s pension, during the

1890s.

Her humanitarian work triumphed

with the opening of the Harriet Tubman Home for the Aged, located on land

abutting her own property in Auburn, which she successfully purchased by

mortgage and then transferred to the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church in

1903. Active in the suffrage movement since 1860, Tubman continued to appear at

local and national suffrage conventions until the early 1900s. She died at the

age of ninety in Auburn, New York.

In the spring of 1944, the National

Council of Negro Women petitioned the U.S. Maritime Commission to name a

Liberty ship in honor of Tubman. The Council sponsored a War Bond drive with

the slogan, “Buy a Harriet Tubman War Bond For Freedom,” and on 3 June the S.S.

Harriet Tubman, the first Liberty ship named for a black woman, was

launched in South Portland, Maine. In 1978, the U.S. Postal Service issued its

first stamp in the Black Heritage Series, commemorating Harriet Tubman. The

Harriet Tubman Home for the Aged in Auburn, New York, received National

Historic Landmark status in 1974, and during the 1990s, her brick residence was

also declared an historic landmark as well. Harriet Tubman’s life was rooted in

an intensely deep spiritual faith and a life long humanitarian passion for

family and community, for whom she risked her very own life, demonstrating an

unyielding, and seemingly fearless, resolve to secure liberty, equality,

justice, and self-determination throughout her long and productive life.

(Launching of the SS Harriet Tubman, June 1944. South Portland Maine. National Archives)